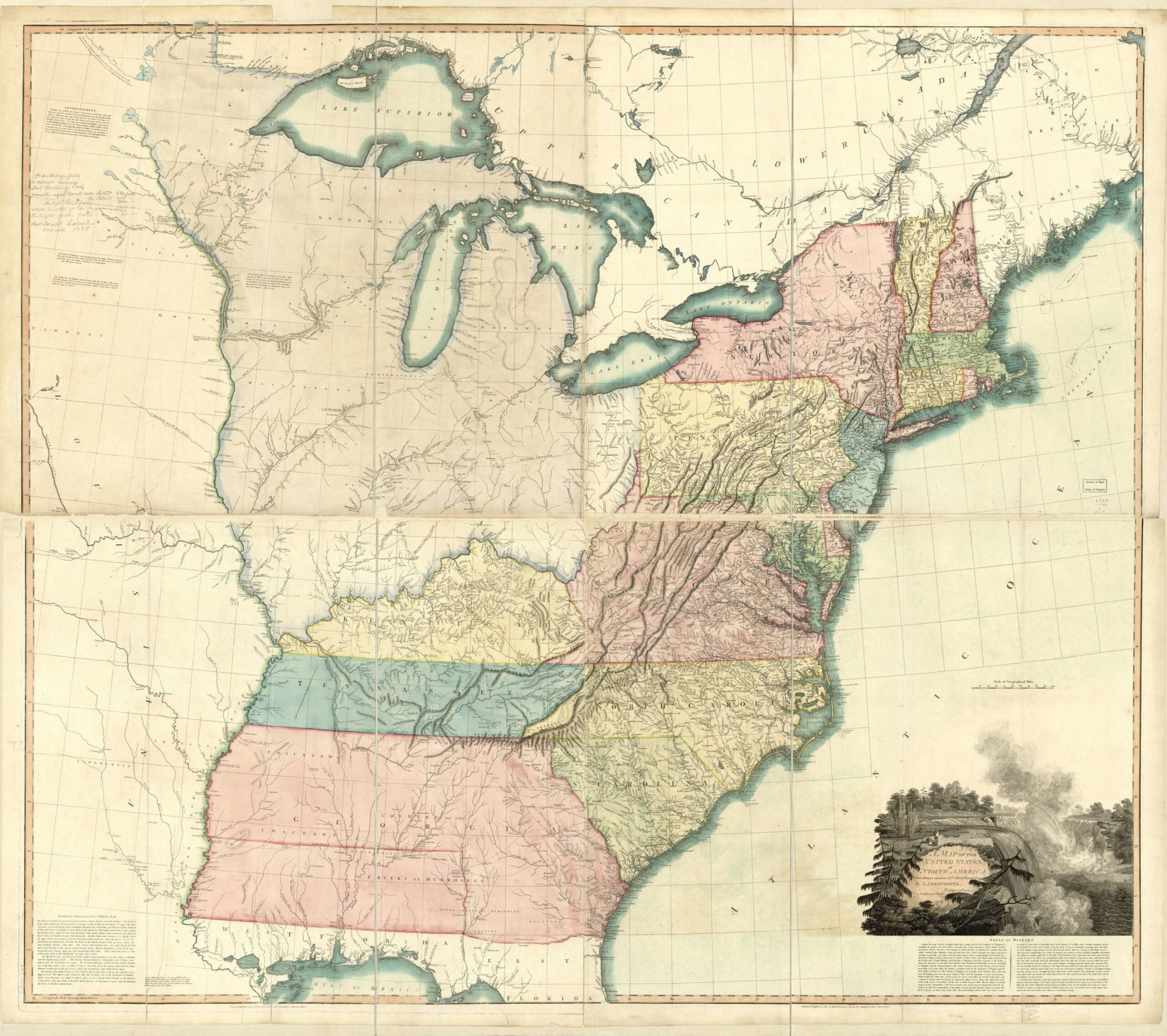

To what extent is the Bill of Rights an individual rights, a group or associational rights, or a states rights document? Why are there ten rather than twelve or seventeen amendments?

Why does the Bill of Rights appear as amendments at the end of the Constitution rather than in the Preamble or in Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution? (See the "Virginia Declaration of Rights and Constitution" (1776), the "New Jersey Constitution" (1776), "The Dissent of the Minority of the Convention of Pennsylvania" (1787), the "Virginia Ratifying Convention" (1788), the "New York Ratifying Convention" (1788), James Madison's "Speech on Amendments to the Constitution" (1789), and "The House Version" (1789).)

No related resources

The American story of the origin and politics of the Bill of Rights involves a conceptual shift of immense consequences: what began in the 13th century as a protection of the few against the one, had become in America by 1791 the protection of the few against a tyrannical legislative majority! And with this conceptual shift, there was also a potential institutional shift away from the legislative branch as the enforcer of rights of the people to the courts as the primary guardians of individual rights. This was one of Thomas Jefferson’s main contributions to the conversation with James Madison, who asked Jefferson who would enforce these paper rights against the majority in his letter to Jefferson in October of 1788. Jefferson also concurred with Madison that the Legislative and not the Executive branch was the most dangerous branch in his letters to James Madison in December 1787 and July 1788. Madison came to recognize that a bill of rights could be more than a “mere parchment” barrier when elected officials overstepped their boundaries (See Representative Madison Argues for a Bill of Rights).

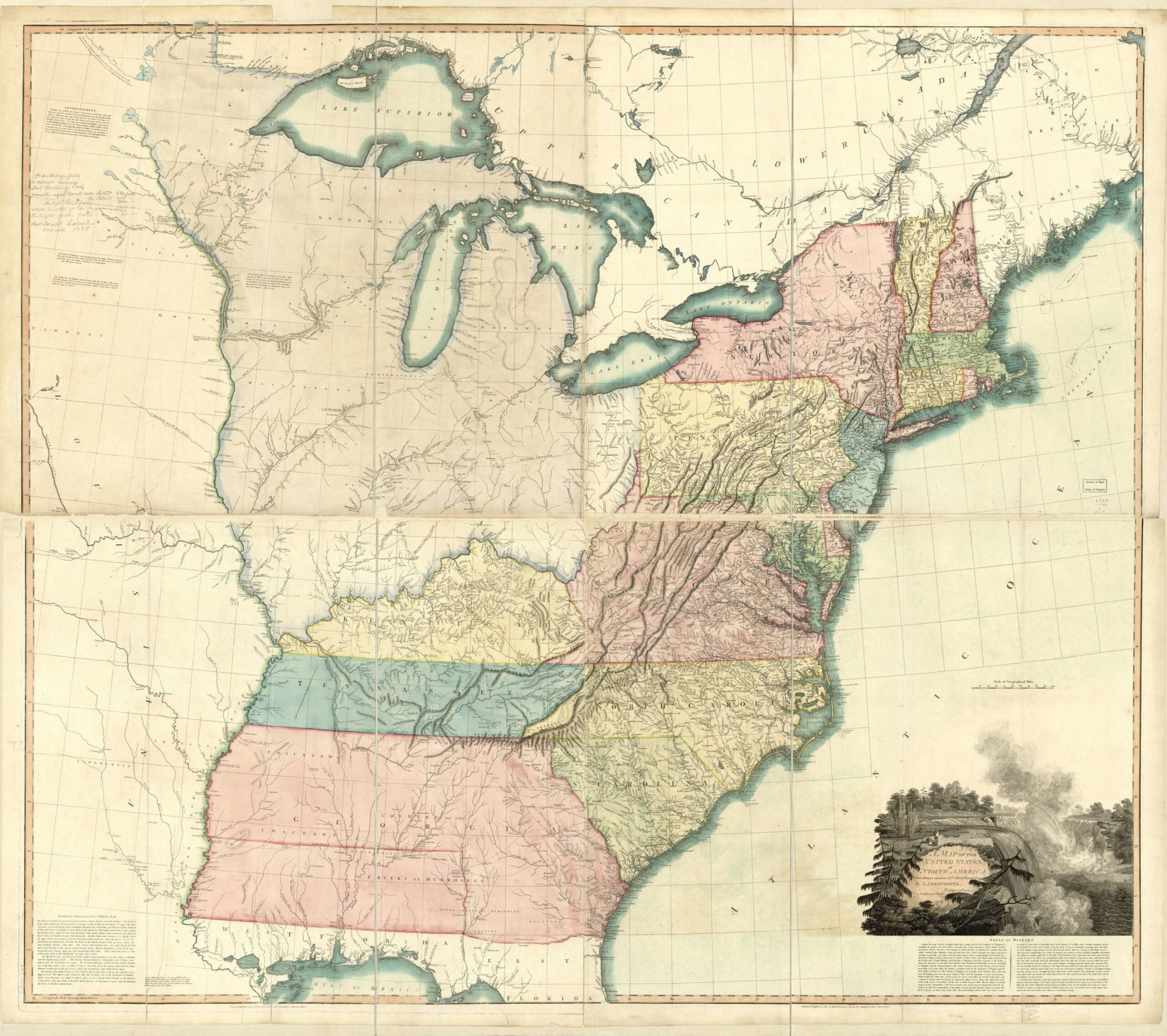

There are no extant documents that record the discussions over the adoption of the Bill of Rights. Secretary of State Jefferson’s Tabulation of the State Votes on Amendments to the Constitution, 1789–91, reads thus: New Jersey (November 20, 1789); Maryland (December 19, 1789); North Carolina (December 22, 1789); South Carolina (January 19, 1790); New Hampshire (January 25, 1790); Delaware (January 28, 1790); Pennsylvania (March 10, 1790); New York (March 27, 1790); Rhode Island (June 11, 1790); Vermont (November 3, 1791); Virginia (December 15, 1791).

Massachusetts, Georgia, and Connecticut did not ratify the first ten amendments at the time they were proposed (but did ratify them in 1939 in commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the adoption of the Bill of Rights by the First Congress). Since three states abstained, all the other eleven states needed to vote yes on every clause for all twelve to pass. Vermont was added as the fourteenth state on March 4, 1791, thus changing the number of states needed to ratify from nine to eleven. If only one of the eleven states objected to one of the twelve amendments then that particular amendment would not passed.

Unanimity over all twelve Amendments did not occur. The first and second amendments went down to defeat. We can conclude that eleven states voted “yes” on all of the other amendments. Thus, the Third Amendment became the First Amendment.

Writing to George Washington on December 5, 1789, Madison explained the “great difficulty” in securing early ratification in Virginia: “The difficulty started against the amendments is really unlucky, and the more to be regretted as it springs from a friend to the Constitution.” Representative John Dawson confirms why Virginia did not ratify earlier in a letter to Madison on December 17, 1789: “The amendments recommended by Congress were taken up and all of them passed our House. . . . The Senate amended the resolution by postponing the consideration of the 3d, 11th, & 12th, until the next session of assembly. . . . We adhered, and so did they. A conference took place, and both houses remained obstinate, consequently the whole resolution was lost, and none of the amendments will be adopted by this assembly.”

—Gordon LloydAmendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment II

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Amendment III

No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Amendment IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Amendment V

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Amendment VI

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

Amendment VII

In Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Amendment VIII

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Amendment IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Amendment X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.